22 Oct Crossing the Rubicon

Superheroes are undeniably outlaws. Operating in the grey area the justice system cannot is in the very nature of the superhero. After all, if the justice system worked as it was there would be no need for such a person. But as threats escalate and corruption seeps in, the necessity of someone willing to break some laws in order to preserve the integrity of the larger, society-binding laws – and indeed the public’s safety, well-being, and way of life – becomes clearer and clearer. So the public, and we as readers, largely condone the illegal actions of heroes serving the greater good: breaking and entering, surveillance, even kidnapping and assault. The one line, however, to which many heroes strictly adhere – and in the case of those who do not is crossed very tentatively – is that of murder.

For those heroes who refuse to cross that line, their reasons are usually quite clear. Batman refuses to cross that line because, in his mind and likely the minds of the people of Gotham, to murder a criminal is to undermine the entire purpose of Batman, which is to sacrifice himself in order to support the enforcement of laws and protection of the innocent, not to replace the rule of law as judge, jury, and executioner. In the case of Superman, his motivation not to kill is even simpler: the only thing that tempers public trust in the Man of Steel is that he doesn’t kill. If he crosses that line, there is no longer a “safety net” between us and one of the most powerful beings on the planet; it would realize all of the paranoia and fear that drives Amanda Waller, Project Cadmus, A.R.G.U.S., and other government agencies built around “Superman contingency”, not to mention Lex Luthor and of course Batman. Conversely, there are plenty of heroes who have chosen to cross that line: Wonder Woman’s upbringing as a warrior provides her with a different perspective on the morality of killing – something which has proven to be very interesting from a story perspective as she contrasts the other two members of the “trinity” (during Infinite Crisis, Superman and Batman cast her aside after she kills Maxwell Lord, even though it was the only way to free Superman from his mind-control).

To kill or not to kill; that is the question. Literally. This dilemma is a cornerstone of the mythology of the detective hero the Question.

The Question first appeared in Blue Beetle #1 in 1967 which was published by Charlton Comics. When DC Comics acquired the rights to several Charlton heroes, the Question was among them. Primarily used as a featured character in other titles, the Question received his own solo title in 1986. This book reintroduced readers to the character: an investigative journalist by the name of Vic Sage, frustrated that he cannot get the answers he is looking for to take down organized crime and corruption. His mentor, Aristotle Rodor, gives him a faceless mask made of pseudoderm (a synthetic skin) which Sage dons to become the Question, in which guise he fights injustice in Hub City – a city described as even more desperate, corrupt, and socially broken than Gotham or Blüdhaven. The series – written by Dennis O’Neil – establishes that in addition to his impeccable investigative skills and knack for detective work, the Question is a skilled martial artist, training in Nanda Parbat with Richard Dragon at the behest of the assassin Lady Shiva.

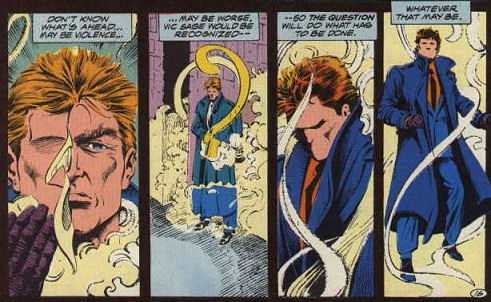

One of the defining characteristics of O’Neil’s The Question is that it established Vic Sage’s long history with anger and resentment. He is notoriously brutal in his dealings with criminals and the corrupt, often tip-toeing the precipitous line of whether or not to kill. Many heroes have struggled with that choice, but what is perhaps most disturbing about the Question is that the main focal point of his inner conflict is that he is intensely curious about killing. He reasons that curiosity is not enough to warrant crossing that line, but he raises a very serious realization for readers: The Question, while fighting on the side of justice, is only tenuously moral. His reluctance to kill is not based in the world of “right” or “wrong”, it is merely awaiting a motivation strong enough to push him over the edge.

That motivation arrives later in the series, when the Question is forced to kill in order to save the daughter of his one-time lover. Though the Question would certainly have saved her without killing had that been an option, he does not hesitate to cross the line once he realizes it is the only way. This moment ought to mark a substantial turning point for a character. When Green Arrow kills Prometheus at the end of Cry for Justice, it marks the start of a downward spiral for the character – no longer able to distinguish when killing is going too far. It ruins his marriage with Black Canary and causes a deep rift between he and many other Justice Leaguers. In many ways, that Green Arrow story was used to portray the “slippery slope” that Batman fears he would succumb to should he ever choose to kill. A similar cycle of destruction is seen in the return of Jason Todd as the Red Hood, in the actions of the Huntress (pre-Flashpoint), and many others. What sets the Question apart is that at that crisis point he makes the same decision to kill – the ultimate decision, really – but when he comes out on the other side, he is not broken or tortured. He isn’t filled with grief or fear or anger. He does not even feel the need to justify his actions by aligning them with a warrior ethos (like Wonder Woman). What sets the Question apart is that after he kills for the first time he feels very little, saying it merely felt ‘lousy’ and later reasoning that should it be necessary in future, he would kill again.

This is a truly dark prospect. For most heroes who kill, the act takes a toll on them physically or mentally. In the case of villains who kill, many at the very least feel a sense of satisfaction – if not outright joy. In either case, the fact that there is an emotional response to the act can at least remind you that you are human, even if the kind of human you are is despicable. But to kill and feel nothing is something removed from the normal discourse of good and evil. Not only does it imply that killing is as easy as washing your hands or brushing your teeth, it states quite clearly that it means just as little. Combined with the Question’s natural affinity for brutality and the increasingly desperate situation in Hub City, the facility of murder to the Question becomes a very troubling philosophical issue. This issue is explored heavily in Watchmen through the character of Rorschach, whose detachment from his own emotions allows him to indiscriminately kill criminals. This is particularly resonant with readers since Rorschach is directly based on the Question, who originally was to appear in the story until editorial concerns forced writer Alan Moore to create a new character.

What the Question represents is something in us which is much more disturbing than evil. In the villains of the DC Universe, we see grotesque extrapolations of the dark parts of our psyche: vanity, rage, greed, and a host of other sins. But no matter how dark the representation, we are constantly reminded of the weight of these sins and the weight of each action taken. Luthor’s jealousy and ambition, for example, are tangible constructs whose presence we feel when we see him scheming against Superman. Each horrific, smiling corpse the Joker leaves behind is a reminder of a family who has lost a mother, a brother, or a best friend. In all cases, actions have emotional consequences that weigh either on the hero, the villain, or the world around them. But for the Question, the weight of his actions does not register. Killing a criminal is no different than a cloud drifting across the sky – neither good nor bad, but rather part of the natural order.

This deconstructs the very paradigms upon which DC’s universe is built: good vs. evil, right vs. wrong, and the idea that all actions resonate. Despite being a hero, I would argue that the Question represents the absolute worst case scenario in terms of human potential: that we disconnect from our emotional responses. That we view morality as an arbitrary social construct. Even if that is truly the case, our society is built on the agreed upon notion that we must accept certain arbitrary restrictions for the sake of order. If we can no longer count on our actions to mean something, to others or to ourselves, then how can we discern which actions are to be discouraged rather than condoned?

That is the question.

** This article was originally published on Modern Mythologies **

No Comments