19 Mar Use It or Lose It

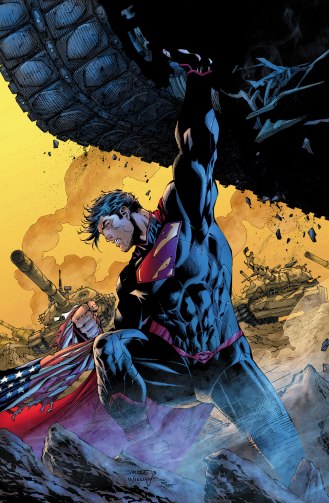

If Superman is so incredibly strong, how is it that he’s in such muscular shape?

It sounds like a silly question, but it comes from a place of extremely genuine curiosity. Scientifically speaking, building muscle requires us to put some strain on our bodies by lifting (curling, pressing, pulling, etc.) weights at the limit of our strength. Working out with low weights can tone muscles but doesn’t do much in terms of making them larger. By that logic, what possible workout is there that could make Superman more than a stringy, well-toned marathon runner?

Unfortunately, there’s not much in the way of an interesting answer to that question (“because it’s a comic book” comes to mind), though it does point to an interesting gap in the mythology of superheroes; while we encourage characters’ personalities to evolve, we view their physicality as static. We see heroes and villains gain their powers or train to become the legends they are, but we never consider the maintenance of those skills or that training. The primary editorial reason for this is that watching routine workouts or exercises is not, in the strictest sense of the word, the stuff of thrilling narrative. But mythologically this leaves a rather large gap – one that separates the acquisition of skill or power from the use of said abilities.

There are some exceptions to this, of course. There is a tendency to focus on Jason Rusch providing Ronnie Raymond with the scientific knowledge necessary to use Firestorm’s powers efficiently. Likewise, television shows such as Arrow and The Flash put great emphasis on the increasing skill and training of their respective heroes. And yet, this still constitutes little more than the development side of the equation. Even in the case of the Batman, whose harrowing training (both of himself and his many protégés) is legendary unto itself, is in many ways assumed to keep up his incredible athleticism and intellect simply by being a superhero, as opposed to maintaining his abilities through training. In general, training is depicted in comic books as a means to an end and once that end is reached (the character gains their powers or skills) it is forgotten about.

There is, however, one hero whose abilities depend on regular maintenance, and whose mythology is built around this concept. That hero is the Elongated Man.

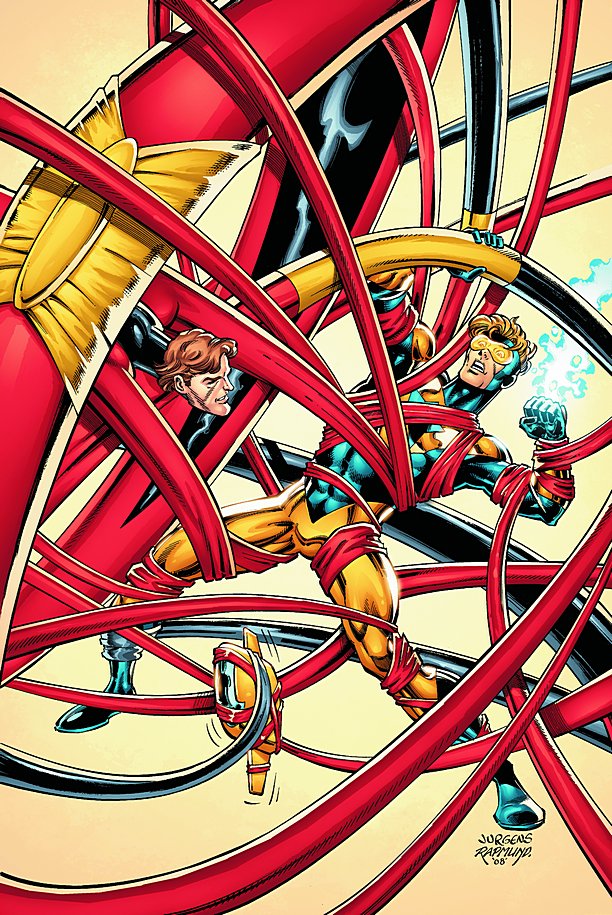

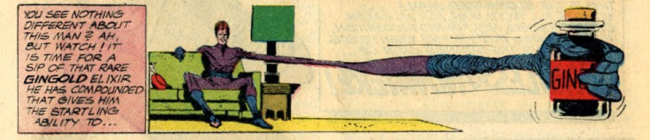

Otherwise known as Ralph Dibny, the Elongated Man is a master detective who possesses the power to stretch any part of his body to incredible proportions. This same power grants him superhuman durability and flexibility, allowing him to change his shape, size, and density at will. Unlike fellow stretching hero Plastic Man – the molecules of whose body were transformed into actual malleable plastic – the Elongated Man gains his abilities thanks to a latent metagene which he triggered with a special gingo extract (alternatively referred to as “gingold”) he developed himself.

There are many reasons why the Elongated Man is important to the mythology of the DC Universe. His marriage to Sue Dibny is a rare example of a superhero succeeding romantically. Likewise, he gave up his secret identity, operating openly as Ralph Dibny, the Elongated Man. Both of these are relatively rare occurrences in superhero comic books, but another unique property of the Elongated Man is how, despite being a metahuman, his superpowers depend entirely on him continuing to drink the gingo extract. The properties within the gingo are what activate his latent metahuman powers, so if Ralph does not consistently drink the extract every two or three days, he begins to lose the ability to stretch. Though frequently mentioned throughout his various appearances, this was eventually proven following the events of Identity Crisis, when Ralph gave up being the Elongated Man after his wife Sue was murdered. He stopped taking the gingo extract and soon after lost his stretching powers.

Of course, there are other characters who derive their powers through consistent consumption of other compounds. Hourman gains one hour of strength, speed, and durability thanks to the Miraclo pills in his possession. Likewise, Bane enhances his strength to superhuman proportions through the use of the super-steroid Venom. The differences between these characters and the Elongated Man are two-fold: firstly, there is an angle of addiction to both Miraclo and Venom that is not present in gingo; and secondly (and arguably more importantly), neither Hourman nor Bane have any inherent powers. In both of their cases, there is nothing of their incredible abilities naturally present within them. The drugs they consume literally give them their powers. This is vastly different to the Elongated Man, whose stretching powers are inherent to him, found in his metagenetic mutation. It just so happens that unlike other metahumans, the Elongated Man’s metagene is not dominant, and so it requires the gingo extract to activate it and allow those powers to manifest themselves. From a metaphorical perspective, this is much like how one would expect a character to build and maintain muscle: the potential for that muscle growth and strength resides within the character but it takes consistent stimulation of those muscles in order for that potential to be reached.

While it may seem a strange element of the character to highlight – especially given his other not insignificant contributions to the DC Universe – there is something extraordinarily important in the Elongated Man’s use of gingo. Ralph Dibny drinking the gingo extract is a metaphor for the continuous training required to maintain a certain physical ability. It both unlocks and supports his genetic and biological abilities, and lapses in that routine have a direct effect on the strength and potency of those abilities. The Elongated Man is a very tangible representation of this metaphor and plays an intriguing role within the mythology of superhero comics. It is through him and the gingo extract that we are reminded that, like personality, the physicality of a character is not static. It requires upkeep. The work doesn’t stop once you become a hero; rather, that is when the real work begins.

** This article was originally published on Modern Mythologies.

No Comments